Thursday, January 7, 2021

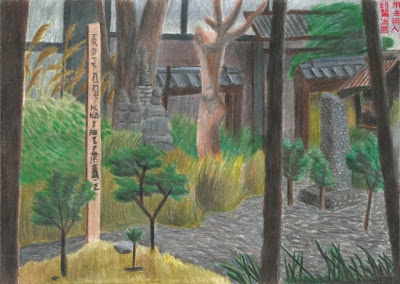

Ryokan no Shinrin

Since I've come back to Omaha for the winter, I've been watching a bunch of Zatoichi films. The main character is a blind masseur/gambler/swordfighter named Zatoichi, a former yakuza who can't seem to leave his past behind no matter how hard he tries. He's also preposterously good at swordfighting, ending dozens of mooks onscreen in dozens of seconds, slicing candles and handing the lit tips over to someone on swordpoint, and slashing the sake bottles of yakuza bosses mid-drink.

The series of movies and, later, television shows, is immensely entertaining, and the writers found ways to keep the formula fresh for years. They were able to release a movie every several months; presumably they could shoot on location, and the hardest part would be choreographing the fight scenes. These movies were probably not difficult or expensive to make, yet quite good anyway. I feel like the inverse is true today; we have millions of dollars to drop on CGI budgets, yet those effects are used as a crutch, and scripts are worse than ever.

But probably my favorite thing about the Zatoichi series is the attention paid to the look of the settings. It's easy to miss if you're sucked in by the plot or the fight scenes, but the visual aesthetic of the whole series is as elegant and understated as Tokugawa Japan itself. Zatoichi finds himself invariably helping the helpless either in some rural forest inn ("Ryokan no Shinrin," the title of this piece, translates as "Forest Inn") or crushing greedy yakuza in some breathtaking mountain village as snow falls, or rescuing a young lady sold into prostitution in some vividly-lit brothel district. It inspired me to draw some of these background scenes; I may yet draw more.

One final note about this piece: discerning readers may not that the way I signed my name in Japanese is different this time. Ideally, one isn't supposed to sign one's name in katakana script, as I did for the Maitreya Buddha, and usually only women will sign their name in hiragana script. The formal kanji script, which is directly ported from Chinese, is preferred. Kanji ideographs are selected based on the sounds of their words in spoken Japanese. My name remains fundamentally a gaijin one barely translatable into a Japanese syllabary, but anyone who can read kanji can probably have a good guess at my real name now. Fortunately, that describes almost none of this blog's readership; it doesn't even describe me. I had to look this up.

A cool aspect of kanji script, though, is that it is ideographic. There are several different words to choose from to represent each syllable in the Japanese version of my name. So I not only translated for sound, but also for literal meaning. My real name means something like "Prime Minister / Strong Ruler" when translated to modern English, but us Anglophones don't give a whole lot of thought to the meaning behind our names so this aspect of naming is pretty irrelevant to us. I was rather surprised when I was able to translate this meaning into kanji a whole lot more directly than I was able to translate the sound of the syllables. Language is a fascinating thing.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Spam and arrogant posts get deleted. Keep it comradely, keep it useful. Comments on week-old posts must be approved.